Swami Veda Bharati's "Shodasi"

|

| The body was put in a box and then slid along bamboo tracks into the deeper channel of the Ganges. |

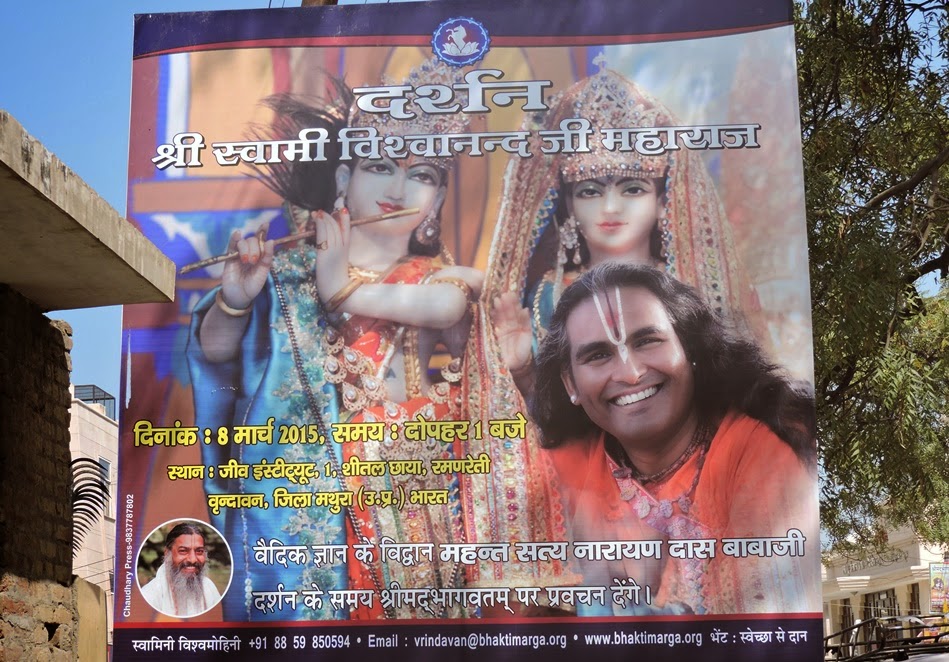

So today (the 29th) was Swamiji's Shodasi, i.e., the end of the official mourning period after his jala-samadhi. Plenty of sadhus from the various akharas showed up. Swami Satyamitrananda Giri was the chief guest and he spoke very nicely in praise of Swamiji and of their friendship. He also said some things about Guru-tattva and urged his disciples onward in their sadhana. But clearly his most important act was to verbally confirm Swami Ritavan Bharati's role as Swamiji's successor and to physically garland him.

Nearly all the other prominent sants and sannyasis present, which included the head of the Niranjani Akhara and several other Mahamandaleshwars spoke of the succession and how Swami Ritavan would need support -- just like Krishna was doing all the heavy lifting at Govardhana, but the other cowherds still lifted their sticks into the base of the hill out of a desire to help.

Obviously the role of the Akhara is primordial in legitimizing successions. Being a foreigner, Swami Ritavan will have to "prove" himself in some ways, and the cultural barriers may be challenging for him. I can see that when Swamiji said Swami Ritavan's work had just begun, he wasn't kidding. Swami Ritavan very cleverly, I thought, declared appreciation for and friendship with Swami Abhishek Chaitanya Giri, a young up-and-coming Mahamandaleshwar, and asked him to be a satya mitra himself -- in helping him to navigate some of those waters I would think.

Evidently Swami Veda wanted to keep a connection with the Akhara samaj and traditions so that the Western influences in the ashram and wider association will always have the mitigating influence of the wider Indian spiritual society and its leadership.

I was given two minutes to say a few things. I have been distilling my thoughts on Swamiji as I went through this two week mourning period in the company of his disciples and admirers, participating in the Gayatri yajna and doing a sustained meditation on my personal relationship and experiences with him and their effects on me. A person's power is evident in the effects he leaves behind.

Swamiji's last disciple was a Muslim woman who had come to spend the Ramadan fast in silence at the ashram. I don't know how she got there, but once she was there Swamiji took special interest in her progress, even though he knew she was not yet prepared for such a practice. When she ran into difficulty, she decided to leave before the end of the thirty days, so Swami called her to his room and gave her initiation in a Muslim mantra, probably something from a Sufi tradition, with which he was well familiar. And he gave her some instructions to practice. That very night he left his body.

I feel this reveals something important about what Swamiji's efforts had been in life. He, in the way of a follower of Patanjali rather than Shankara, believed that religions are a superstructure that directs towards self-realization as pure soul, the purusha separate from all impositions including those of religion. This is also why he made and valued his many friendships with Sufis and Christian mystics and participated in many interreligious efforts at peace-making.

His conviction was that yoga is the science of direct perception of the self, ātma-sākṣātkāra, which can only be achieved through meditation: Yoga IS samadhi.

Whenever Swamiji led a meditation, his aim was to lead people as directly as possible to that place of the self. And since mantra is an important part of that scientific process, he always advised that one use a mantra that aligns with their faith, with their own highest ideals.

Then when one has a taste for samadhi, then one reframes his sectarian religion around the transformations that are effectuated by the process itself. But when on the level of communication in the worldly environment, it emphasizes through realization the common threads that join all the different cultural manifestations rather than the particularities that separate one from another.

This is why it is scientific, according to him. But when one's religious understanding has been transformed by insight into its deeper meanings through yogic insight, then the religion itself becomes rejuvenated. Because the sense of unity that transcends all difference is the meaning of love. And it is love that gives life to a religion, not dogma.

I probably would have said it better in the English, and no doubt I already improved on it a bit. But I am happy to say that one or two people did note the subject of what I spoke on rather than the quality of my Hindi, which is still horrendously below the standard for which I strive.

Angiras, Swamiji's son, came up afterward and thanked me for highlighting this topic, which he agreed was central to Swamiji's entire project. He enthusiastically pointed to the plaques on the wall of the main building which have the "mahavakyas" of Judaism, Islam, Zoroastrianism and Sikhism printed on them. I answered, "Look, I am wearing my Vaishnava tilak. It is a question of knowing when to be one and when to be different."

Swamiji loved his Vedic heritage. For the two weeks after his disappearance the ashram was filled with a beautiful Gayatri yajna (yajñānāṁ japa-yajño'smi) in which I participated with my Kama Gayatri japa, with several hours of japa each day and completed with daily arati and then fire yajnas on the last two days. Ten brahmins performed the yajna with great expertise in their recitals and full-throated chanting of Vedic mantras, adding dimensions of power to the japa-yajna.

Swamiji even said to me somewhat confidentially not long before I left Rishikesh the previous month -- the last time I saw him -- that he was really a "Vedic scholar" and that he wanted to get back to that before he died! [He was always making plans right to the very end; his multidimensional ambitions were unlimited!]

But that was still the external part of his life, the internal was samādhi. And his aim was to get others to also see that unless they found that internal side -- no matter what their external sectarian rites, rituals and dogmas -- they would always get caught up in the upādhis and be in friction with themselves and others.

From the Vaishnava perspective I see it this way: Brahman, Paramatma, and Bhagavan are the three dimensions of the Absolute. Brahman is God in the most "general" or universal (sāmānya) category. Since Brahman IS the Atman, so there is no conflict between Vedanta and Yoga. Bhagavan, however, even as existing in transcendence is "particular" (viśeṣa), as are the various concepts of God as viewed from within the material manifestation, i.e., covered by the curtain of the gunas of prakriti. Bhagavan is only revealed in Samadhi.

When you attain kaivalya, Swamiji says, who knows what happens? But whatever happens there, when one returns from samādhi to vyutthāna, i.e,. when one goes from internal to external consciousness, however slight that movement, one returns to the names and forms to which he is accustomed, i.e, the particulars, but he knows them as particulars and does not claim universal truth for particulars. Particulars are always subjective. Even so, for the person in knowledge, the particulars are imbued with the vibrant life of direct perception -- and their universal meaning is known and understood: brahma-bhūtaḥ prasannātmā... mad-bhaktim labhate parām.

But the underlying basis for all kinds of unity really begins with the dropping of upādhis. The conscious dropping of all superficial distinctions.

If you want to understand Krishna bhakti, you need this dimension also. Otherwise, you fall so easily into the various traps of pṛthak dṛṣṭi, seeing oneself as separate from the Whole, separate from love.

|

| Swami Ritavan Bharati |

Comments